Elaine Perlman forwards the following discussion points:

Coalition

to Modify NOTA Talking Points

modifyNOTA.org

What is the Coalition to Modify

NOTA proposing? The Coalition to Modify NOTA proposes providing a $50,000

refundable tax credit to remove all disincentives for American non-directed

kidney donors who donate their kidney to a stranger at the top of the kidney

waitlist in order to greatly increase the supply of living kidney transplants,

the gold standard for patients with kidney failure.

What is the value of a new kidney? The value

of a new kidney, in terms of quality of life and future earnings potential, is

between $1.1 million

and $1.5 million.

What is the American kidney

crisis? Fourteen Americans

on the waiting list for a kidney transplant die each day. That number does not

include the many kidney failure patients who are not placed on the waiting list

but would have benefited from a kidney transplant if we had no shortage. The total

number of Americans with kidney failure will likely exceed one million by 2030.

Why not

rely on deceased donor kidneys to end the shortage? A living

kidney transplant lasts on average twice as long as a deceased donor kidney.

Fewer than 1 in 100 Americans die in a way that their kidneys can be procured.

Currently, the 60% of

Americans who are registered as deceased donors provide kidneys for 18,000

Americans annually. Even if 100% of Americans agreed to become organ donors,

this would raise donations by only about 12,000 per year. In the

USA, 93,000

Americans are on the kidney waitlist. A total of 25,000 people

are transplanted annually, two-thirds from deceased donors and one-third from

living donors. The size of the waitlist has nearly doubled in the

past 20 years, while the number of living donors has not increased.

What is the

extra value that non-directed kidney donors provide? Non-directed

kidney donors often launch kidney chains that can result in a multitude of Americans receiving

kidneys. Fewer than 5% of all living kidney donations are from

non-directed kidney donors who are an excellent source of organs for

transplantation because they are healthier than the general population.

How much

does the taxpayer currently spend on dialysis? Kidney

transplantation not only saves lives; it also saves money for the taxpayer. The

United States government spends nearly $50 billion

dollars per year (1% of all $5 trillion collected in annual taxes) to pay

for 550,000 Americans

to have dialysis, a cost of approximately $100,000 per year per patient, a

treatment that is far more expensive than transplantation.

How many

more lives will be saved with the refundable tax credit for non-directed

donors? The number of non-directed donors increased from 18 in 2000 to

around 300 each year. After our Act becomes law, we estimate that we will add

approximately 7,000 non-directed donor kidneys annually. That is around 70,000

new transplanted Americans by year ten.

How much

tax money will be saved once the Act is passed? The

refundable tax credit will greatly increase the number of living donors who

generously donate their kidneys to strangers. We estimate that in year ten

after the Act is passed, the taxpayers will have saved $12 billion.

What is a

refundable tax credit? A refundable tax credit can be accessed by both

those who do and those who do not pay federal taxes.

What do

Americans think about compensating living kidney donors? Most

Americans favor compensation for living kidney donors to increase

donation rates.

Who is able to donate their

kidneys? Donation requires potential organ donors to undergo a

comprehensive physical and psychological evaluation, and each transplant center

has its own rigorous criteria. Only around 5% of those who pursue evaluation

actually end up donating, and only about one-third of Americans are healthy

enough to be donors. Providing financial incentives will encourage more

Americans to donate their kidneys to help those with kidney failure.

Do kidney donors currently have

expenses that result from their donation? The medical costs of

donation are covered by the recipients' insurance, but donors are responsible

for providing for the costs of their own travel, out-of-pocket expenses, and

lost wages. Programs like the federal NLDAC and NKR's Donor Shield can help

offset these costs, making donation less expensive.

Is it moral to compensate kidney

donors? Compensation for kidney donors can be viewed as a way to

address the current kidney shortage and save lives. Americans are compensated

for various forms of donation such as sperm, eggs, plasma, and surrogacy, all

of which involve giving life.

How long do we need to compensate

living kidney donors? Compensation should continue until a xenotransplant or advanced

kidney replacement technology becomes available. In the meantime, it's crucial

to prevent further loss of lives due to the shortage.

Will incentivizing donors

undermine altruism? Financial compensation for donors can coexist

with altruism. Donors can opt out of the funds from the tax credit or choose to

donate those funds to charity. The majority of donors support financial

compensation, and relying solely on altruism has led to preventable deaths.

In addition to ending the kidney

shortage, what are other benefits of the Act? The Act can help combat

the black market for kidneys and reduce human trafficking because we will have

an increased number of transplantable kidneys. It can also motivate individuals

to become healthier to pass donor screening, potentially further reducing

overall healthcare costs.

Why provide non-directed donors

with a refundable tax credit of $50,000? The compensation is designed to

attract those who are both healthy and willing to donate. Given the commitment,

time, and effort involved in the donation process, this compensation recognizes

the value of those who save lives and taxpayer funds.

When more donors step forward,

can transplant centers increase the number of surgeries? There is

considerable unused capacity at most U.S. transplant centers, and increasing

the number of donors is likely to lead to more surgeries. The goal is to

perform more kidney transplants and reduce the waitlist, benefiting patients in

need.

In what way does the Act uphold The Declaration of Istanbul? While

the Act deviates from one principle of the Declaration of Istanbul by offering

compensation, it aligns with the other principles and is expected to

standardize compensation and reduce worldwide organ trafficking.

What about dialysis as an

alternative to transplant? Dialysis, while a treatment option,

can be a challenging and uncomfortable process for patients. For those who

could have been transplanted if there were no kidney shortage, dialysis can

result in needless suffering and an untimely death.

Why not compensate living liver

donors? Liver donation is riskier and not as cost-effective as kidney

donation. While the Act currently focuses on kidney donors, it's possible that

compensation for liver donors could be considered in the future.

What about the argument that

providing an incentive to donate will exploit the donors, especially low income

donors?

Primarily middle and low income

kidney failure patients are dying due to the kidney shortage. People with lower

incomes tend to have social networks with fewer healthy people because health

is related to income level. In addition, being placed on a waitlist often costs

money. Kidney donation also costs money, an estimated 10% of annual

income. The refundable tax credit will help low income donors and recipients

the most by making donation affordable and increasing the number of kidneys for

those waiting the longest on the waitlist, frequently middle and low income

Americans. The tax credit aims to help those most affected by the kidney

shortage, as poorer and middle-income individuals often bear the brunt of the

kidney crisis’s consequences. The Act will level the playing field, making it

easier for those at all income levels to receive a life-saving kidney.

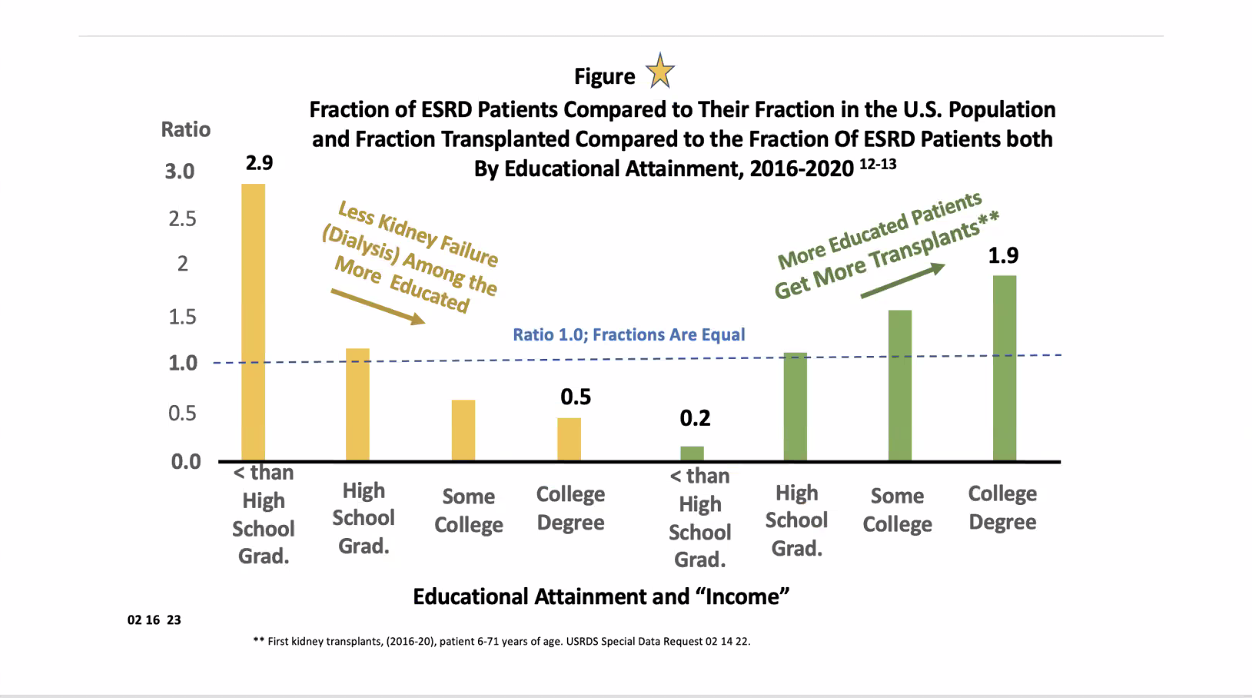

Please examine this chart: