Since the beginning of the year, I've been sent several Data Use Agreements from organizations interested in the possibility of sharing some of their data for research purposes. I've had to decline the opportunity more than once, because of publication restrictions that conflict with Stanford research policies (and those of most other universities, I think, out of concern for academic freedom, and to keep academic publications free from selection bias concerning the research findings).

The relevant Stanford policies are here: https://doresearch.stanford.edu/policies/research-policy-handbook/conduct-research/openness-research

The most relevant paragraphs are these:

"C. Publication Delays

"In a program of sponsored research, provision may be made in the contractual agreement between Stanford and the sponsor for a delay in the publication of research results, in the following circumstances:

"For a short delay (the period of delay not to exceed 90 days), for patenting purposes or for sponsor review of and comment on manuscripts, providing that no basis exists at the beginning of the project to expect that the sponsor would attempt either to suppress publication or to impose substantive changes in the manuscripts.

"For a longer delay in the case of multi-site clinical research (the period of delay not to exceed 24 months from the completion of research at all sites), where a publication committee receives data from participating sites and makes decisions about joint publications. Such delays are permitted only if the Stanford investigator is assured the ability to publish without restrictions after the specified delay."

**************

Alex Chan points me to this article in Science by some of our Stanford colleagues:

Waiting for data: Barriers to executing data use agreements by Michelle M. Mello, George Triantis, Robyn Stanton, Erik Blumenkranz, David M. Studdert, Science 10 Jan 2020: Vol. 367, Issue 6474, pp. 150-152 DOI: 10.1126/science.aaz7028

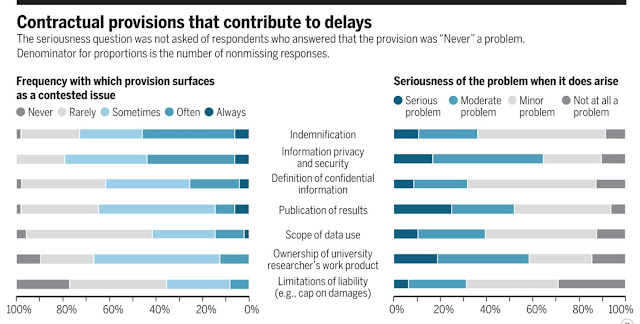

Here's a figure from the paper that makes clear that concerns about publication often are serious obstacles (and that concerns about indemnification clauses are frequent obstacles).

"The third set of issues relates to clashes between DUA negotiators over what is and is not acceptable in the contract. Negotiators reported that the most common and serious of these substantive issues related to provisions concerning information privacy and security, indemnification, and the definition of confidential information; provisions concerning publication rights and ownership of academic researchers' work product were less commonly in dispute but serious problems when they were. These are no mere matters of “legalese”; each implicates potentially important risks to the university and faculty member.

...

"Indemnification is another actionable area. At least where low-risk data are involved, university contract negotiators may be spending more time on these provisions than is warranted. If good privacy and security protections are in place, the risk of a data breach is low, and haggling over who pays in the unlikely event of a breach that causes harm should not obstruct timely data transfers for research. Yet, negotiators at 13 of 48 universities had walked away from a negotiation because of indemnification issues.

"When it comes to provisions safeguarding publication rights and ownership of faculty members' work product, on the other hand, universities must remain resolute. These provisions implicate core values of the university and of open science. A potential strategy for minimizing haggling over non-negotiable issues is for universities as a group to more clearly signal their unified position. Existing university policies setting forth institutional commitments to academic freedom and policies concerning IP are helpful in communicating norms, but even more helpful would be a universal DUA template."

No comments:

Post a Comment