Wednesday's program

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

Algorithms, Approximation, and Learning in Market and Mechanism Design at SLMath Berkeley this week--Wednesday

Tuesday, November 7, 2023

Algorithms, Approximation, and Learning in Market and Mechanism Design at SLMath Berkeley this week--Tuesday

Here's Tuesday's program

Monday, November 6, 2023

Algorithms, Approximation, and Learning in Market and Mechanism Design at SLMath Berkeley this week--Monday

Sunday, November 5, 2023

Deceased organ donation in the Economist (article and letter to the editor)

Here's a recent article on deceased organ donation, in The Economist, followed by a letter to the editor from Alex Chan and me.

In America, lots of usable organs go unrecovered or get binned. That is a missed opportunity to save thousands of lives

"More than four-fifths of all donated organs and two-thirds of kidneys come from dead people (who must die in hospital); living donors can give only a kidney or parts of a lung or liver. Whereas some countries, such as England, France and Spain, have an opt-out model, in America donors must register or their families must agree. Persuading them will always be hard: Dr Karp’s hospital gets consent from about half of potential donors.

...

"Responsibility lies partly with some of the 56 nonprofit Organ Procurement Organisations (opos), like LiveOnNY, that do the legwork. Brianna Doby, a researcher and consultant, advised Arkansas’s opo in 2021 and was astounded to learn that most calls about potential donors went unanswered outside the nine-to-five workday and at weekends. Other opos, by contrast, sent staff to hospitals within an hour of an alert about a prospective donor.

...

"Yet unrecovered organs are not the only reason America could do more transplants. A surprising number of organs from deceased donors end up in the rubbish: more than a quarter of kidneys and a tenth of livers last year.

...

"Hospitals are often risk-averse, too. Discard rates are higher for organs of lower quality.

...

"For elderly recipients, getting older or otherwise risky kidneys generally means better odds of survival than staying on dialysis. But hospitals dislike using them for two reasons. First, they can lead to more complications and thus require more resources, eating into margins. Second, if the recipient dies soon after the transplant, hospitals suffer—a key measure used to evaluate them is the survival rate of recipients a year after transplant. According to Robert Cannon, a liver-transplant surgeon at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, hospitals succeed by being excessively cautious and keeping patients with worse prospects off waiting lists."

#########

And here's our followup letter to the editor, published November 2:

"More than 110,000 Americans are waiting for an organ transplant and over 5,000 died waiting for an organ in 2019. Close to 6,000 recovered organs were discarded. “Wasted organs” (September 23rd) correctly pointed out that the responsibility lies in part with non-profit Organ Procurement Organisations and in part with the excessive caution exercised by transplant centres when deciding who to conduct transplants for and which kidneys to use.

"Numerous initiatives in Congress, and more proposed by various non-governmental agencies, such as the Federation of American Scientists and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, among others, have been focused on tweaking how the performance of organ procurers and transplant centres should be measured while keeping in place the system that put us in today’s quagmire. As we indicate in our recent paper (conditionally accepted at the Journal of Political Economy), such approaches that keep regulations fragmented are bound to be inefficient, given that the incentives and opportunities facing organ procurers and transplant centres are intertwined.

"We show that “holistic regulation”, which aligns the interests of organ procurers and transplant centres by rewarding them based on the health outcomes of the entire patient pool, can get at the root of the problem. This approach also leads to more organ recoveries while increasing the use of organs for sicker patients who otherwise would be left without a transplant.

"In the end increasing access to kidney transplantation will require the improvement of the entire supply chain of organs. This means boosting donor registrations and donor recoveries from the deceased. It also means increasing living donations, and co-ordinating donations through mechanisms like paired kidney donations and deceased-donor-initiated kidney- exchange chains.

Alex Chan, Assistant professor of business administration, Harvard University

Alvin E. Roth, Professor of economics, Stanford University

####

And here's the paper referred to in our letter, on Alex's website:

Regulation of Organ Transplantation and Procurement: A Market Design Lab Experiment, by Alex Chan and Alvin E. Roth

Abstract: "We conduct a lab experiment that shows current rules regulating transplant centers (TCs) and organ procurement organizations (OPOs) create perverse incentives that inefficiently reduce both organ recovery and beneficial transplantations. We model the decision environment with a 2-player multi-round game between an OPO and a TC. In the condition that simulates current rules, OPOs recover only highest-quality kidneys and forgo valuable recovery opportunities, and TCs decline some beneficial transplants and perform some unnecessary transplants. Alternative regulations that reward TCs and OPOs together for health outcomes in their entire patient pool lead to behaviors that increase organ recovery and appropriate transplants."

Saturday, November 4, 2023

The EU proposes strengthening bans on compensating donors of Substances of Human Origin (SoHOs)--op-ed in VoxEU by Ockenfels and Roth

The EU has proposed a strengthening of European prohibitions against compensating donors of "substances of human origin" (SoHOs). Here's an op-ed in VoxEU considering how that might effect their supply.

Consequences of unpaid blood plasma donations, by Axel Ockenfels and Alvin Roth / 4 Nov 2023

"The European Commission is considering new ways to regulate the ‘substances of human origin’ – including blood, plasma, and cells – used in medical procedures from transfusions and transplants to assisted reproduction. This column argues that such legislation jeopardises the interests of both donors and recipients. While sympathetic to the intentions behind the proposals – which aim to ensure that donations are voluntary and to protect financially disadvantaged donors – the authors believe such rules overlook the effects on donors, on the supply of such substances, and on the health of those who need them.

"Largely unnoticed by the general public, the European Commission and the European Parliament’s Health Committee have been drafting new rules to regulate the use of ‘substances of human origin’ (SoHO), such as blood, plasma, and cells (Iraola 2023, European Parliament 2023). These substances are used in life-saving medical procedures ranging from transfusions and transplants to assisted reproduction. Central to this legislative initiative is the proposal to ban financial incentives for donors and to limit compensation to covering the actual costs incurred during the donation process. The goal is to ensure that donations are voluntary and altruistic. The initiative aims to protect the financially disadvantaged from undue pressure and prevent potential misrepresentation of medical histories due to financial incentives. While the intention is noble, the proposal warrants critical analysis as it may overlook the detrimental effects on donors themselves, on the overall supply of SoHOs, and consequently on the health, wellbeing, and even the lives of those who need them. We illustrate this in the context of blood plasma donation.

"Over half a century ago, Richard Titmuss (1971) conjectured that financial incentives to donate blood could compromise the safety and overall supply. This made sense in the 1970s, when tests for pathogens in the blood supply were not yet developed. But Titmuss’ conjecture permeated policy guidelines worldwide, despite mounting evidence to the contrary. Although more evidence is needed, a review published by Science (Lacetera et al. 2013; see also Macis and Lacetera 2008, Bowles 2016), which looked at the evidence available more than 40 years after Titmuss’ conjecture, concluded that the statistically sound, field-based evidence from large, representative samples is largely inconsistent with his predictions.

"Getting the facts right is important because, at least where blood plasma is concerned, the volunteer system has failed to meet demand (Slonim et al. 2014). There is a severe and growing global shortage of blood plasma. While many countries are unwilling to pay donors at home, they are willing to pay for blood plasma obtained from donors abroad. The US, which allows payment to plasma donors, is responsible for 70% of the world’s plasma supply and is also a major supplier to the EU, which must import about 40% of its total plasma needs. Together with other countries that allow some form of payment for plasma donations – including EU member states Germany, Austria, Hungary, and the Czech Republic – they account for nearly 90% of the total supply (Jaworski 2020, 2023). Based on what we know from controlled studies and from experiences with previous policy changes, a ban on paid donation in the EU will reduce the amount of plasma supplied from EU members, prompting further attempts to circumvent the regulation by importing even more plasma from countries where payment is legal. At the same time, a ban will contribute to the global shortage of plasma, further driving up the price and making it increasingly unaffordable for low-income countries (Asamoah-Akuoko et al. 2023). In the 1970s, it may have been reasonable to worry that encouraging paid donation would lead to a flow of blood plasma from poor nations to rich ones. That is not what we are in fact seeing. Instead, plasma supplies from the US and Europe save lives around the world.

"In other areas, society generally recognises the need for fair compensation for services provided, especially when they involve discomfort or risk. After all, it is no fun having someone stick a needle in your arm to extract blood. This consensus cuts across a range of services and professions – including nursing, firefighting, and mining – occupations, most people would agree, that should be well rewarded for the risk involved and value to society. To rely solely on altruism in such areas would be exploitative and would eventually lead to a collapse in provision. Indeed, to protect individuals from exploitation, labour laws around the world have introduced minimum compensation requirements rather than caps on earnings. In addition, payment bans on donors, even if they’re intended to protect against undue inducements, raise concerns about price-fixing to the benefit of non-donors in the blood plasma market. In a related case, limits on payment to egg donors have been successfully challenged in US courts. 1

"In addition, policy decisions affecting vital supplies such as blood plasma should be based on a broad discourse that includes diverse perspectives and motivations. Ethical judgements often differ, both among experts and between professionals and the general public, so communication is essential (e.g. Roth and Wang 2020, Ambuehl and Ockenfels 2017). Payment for blood plasma donations is an example. We (the authors of this article) are from the US and Germany, countries that currently allow payment for blood plasma donations while most other countries prohibit payment. On the other hand, prostitution is legal in Germany but surrogacy is not, while the opposite is true in most of the US. And while Germany currently prohibits kidney exchange on ethical grounds, other countries – including the US, the UK, and the Netherlands – operate some of the largest kidney exchanges in the world and promote kidney exchange on ethical grounds.

"The general public does not always share the sentiments that health professionals find important (e.g. Lacetera et al. 2016). This tendency is probably not due to professionals being less cognitively biased. In all areas where the question has been studied, experts such as financial advisers, CEOs, elected politicians, economists, philosophers, and doctors are just as susceptible to cognitive bias as ordinary citizens (e.g. Ambuehl et al. 2021, 2023). Recognising the similarities and differences between professional and popular judgements, and how ethical judgements are affected by geography, time, and context, allows for a more constructive and effective search for the best policy options.

"In our view, the dangers of undersupply of critical medical substances, of inequitable compensation (particularly for financially disadvantaged donors), and of circumvention of regulation by sourcing these substances from other countries (where the EU has no influence on the rules for monitoring compensation to protect donors from harm) are at least as significant as those arising from overpayment. Carefully designed transactional mechanisms may also help to respect ethical boundaries while ensuring adequate supply. Advances in medical and communication technologies, such as viral detection tests, can effectively monitor blood quality and ensure the safety and integrity of the entire donation process – including the deferral of high-risk donors and those for whom donating is a risk to their health – without prohibiting payment to donors. Even if it is ultimately decided that payments should be banned, there are innovations in the rules governing blood donation that have been proposed, implemented, and tested that would improve the balance between blood supply and demand within the constraints of volunteerism; non-price signals, for instance, can work within current social and ethical constraints.

"As the EU deliberates on this legislation, it is imperative to adopt a balanced, empirically sound, and research-backed approach that considers multiple effects and promotes policies to safeguard the interests of both donors and recipients.

References

Asamoah-Akuoko, L et al. (2023), “The status of blood supply in sub-Saharan Africa: barriers and health impact”, The Lancet 402(10398): 274–76.

Ambuehl, S and A Ockenfels (2017), “The ethics of incentivizing the uninformed: A vignette study”, American Economic Review Papers & Proceedings 107(5), 91–95.

Ambuehl, S, A Ockenfels and A E Roth (2020), “Payment in challenge studies from an economics perspective”, Journal of Medical Ethics 46(12): 831–32.

Ambuehl, S, S Blesse, P Doerrenberg, C Feldhaus and A Ockenfels (2023), “Politicians’ social welfare criteria: An experiment with German legislators”, University of Cologne, working paper.

Ambuehl, S, D Bernheim and A Ockenfels (2021), “What motivates paternalism? An experimental study”, American Economic Review 111(3): 787–830.

Bowles S (2016), “Moral sentiments and material interests: When economic incentives crowd in social preferences”, VoxEU.org, 26 May.

European Parliament (2023), “Donations and treatments: new safety rules for substances of human origin”, press release, 12 September.

Iraola, M (2023), “EU Parliament approves text on donation of substances of human origin”, Euractiv, 12 September.

Jaworski, P (2020), “Bloody well pay them. The case for Voluntary Remunerated Plasma Collections”, Niskanen Center.

Jaworski, P (2023), “The E.U. Doesn’t Want People To Sell Their Plasma, and It Doesn’t Care How Many Patients That Hurts”, Reason, 20 September.

Lacetera, N, M Macis and R Slonim (2013), “Economic rewards to motivate blood donation”, Science 340(6135): 927–28.

Lacetera, N, M Macis and J Elias (2016), “Understanding moral repugnance: The case of the US market for kidney transplantation”, VoxEU.org, 15 October.

Macis M and N Lacetera (2008), “Incentives for altruism? The case of blood donations”, VoxEU.org, 4 November.

Roth, A E (2007), “Repugnance as a constraint on markets”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(3): 37–58.

Roth A E and S W Wang (2020), “Popular repugnance contrasts with legal bans on controversial markets”, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(33): 19792–8.

Slonim R, C Wang and E Garbarino (2014), “The Market for Blood”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(2): 177–96.

Titmuss, R M (1971), The Gift Relationship, London: Allen and Unwin.

Footnotes: 1. Kamakahi v. American Society for Reproductive Medicine, US District Court Northern District of California, Case 3:11-cv-01781-JCS, 2016.

Friday, November 3, 2023

Jobs for economists, so far this year

Here's a preliminary AEA memo on the job market.

"To: Members of the American Economic Association

From: AEA Committee on the Job Market: John Cawley (chair), Matt Gentzkow, Brooke Helppie-McFall, Al Roth, Peter Rousseau, and Wendy Stock

Date: October 26, 2023

Re: JOE job openings by sector, 2023 versus the past 4 years

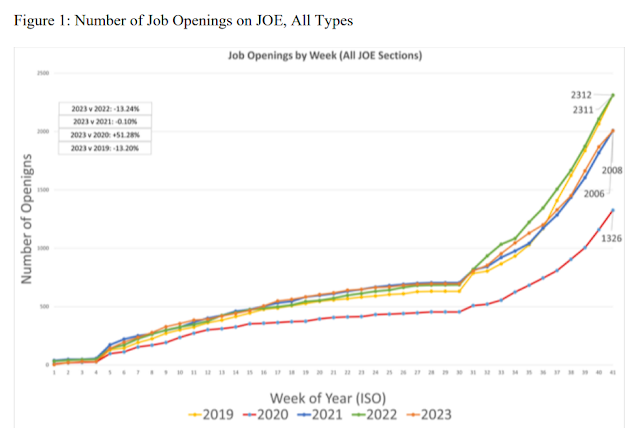

This memo reports the cumulative number of unique job openings on Job Openings for Economists (JOE), by sector and week, compared to the same week in recent years.

...

"Figure 1 (on p. 3) shows the total number of job openings in 2023, compared to recent years. As of the end of week 41, there have been 2,006 jobs listed on JOE since the beginning of 2023, which is 13.2% lower than at the same time in 2022, roughly the same (-0.10% lower) as in 2021, 51.3% higher than this time in 2020 (the worst COVID year), and 13.2% lower than 2019, the last pre-COVID year.

Thursday, November 2, 2023

Jury Finds Realtors Conspired to Keep Commissions High

One of the puzzles of the internet age, when you can take house tours remotely, and see house listings online, is how real estate agents have managed to keep their dominant position in the residential real estate market, including commissions that have remained roughly constant as a percentage of sale price, as sale prices have risen. There's certainly room for economists to investigate the contract forms that are widespread in the industry.

In the meantime, the WSJ has the story from the legal front:

Jury Finds Realtors Conspired to Keep Commissions High. The National Association of Realtors and big residential brokerages were found liable for about $1.8 billion in damages By Laura Kusisto, Nicole Friedman, and Shannon Najmabadi

The verdict could lead to industrywide upheaval by changing decades-old rules that have helped lock in commission rates even as home prices have skyrocketed—which has allowed real-estate agents to collect ever-larger sums. It comes in the first of two antitrust lawsuits arguing that unlawful industry practices have left consumers unable to lower their costs even though internet-era innovations have allowed many buyers to find homes themselves online.

Announced in a packed Kansas City, Mo., courtroom, the verdict came after just a few hours of jury deliberations. The case was brought by home sellers in several Midwestern states."

Wednesday, November 1, 2023

The broken market for antibiotics, continued

Not only is the market for new antibiotics broken, companies that explore them are going broke.

Here's a story from the WSJ:

The World Needs New Antibiotics. The Problem Is, No One Can Make Them Profitably. New drugs to defeat ‘superbug’ bacteria aren’t reaching patients By Dominique Mosbergen

"The push for antibiotics to fight fast-evolving superbugs is snagging on a broken business model.

"Six startups have won Food and Drug Administration approval for new antibiotics since 2017. All have filed for bankruptcy, been acquired or are shutting down. About 80% of the 300 scientists who worked at the companies have abandoned antibiotic development, according to Kevin Outterson, executive director of CARB-X, a government-funded group promoting research in the field.

...

"The reason, the companies say: They couldn’t sell their lifesaving products because the system that produces drugs for cancer and Alzheimer’s disease—which counts on companies selling enough of a new treatment or charging a high enough price to reward investors and make a profit—isn’t working for antibiotics.

New antibiotics are meant to be used rarely and briefly to defeat the most pernicious infections so bacteria don’t develop resistance to them too quickly. Companies have priced them at 100 times as much as the generic antibiotics doctors have prescribed for decades that cost a few dollars per dose. Most have sold poorly.

...

"Most large pharmaceutical companies aren’t developing antibiotics. Several have closed or divested antibiotic development programs. “There’s no profitability,” Hyun said. "